What's new arround internet

| Src | Date (GMT) | Titre | Description | Tags | Stories | Notes |

| 2024-10-25 10:30:02 | The Windows Registry Adventure # 4: Hives and the Registry Mayout The Windows Registry Adventure #4: Hives and the registry layout (lien direct) |

Posted by Mateusz Jurczyk, Google Project Zero

To a normal user or even a Win32 application developer, the registry layout may seem simple: there are five root keys that we know from Regedit (abbreviated as HKCR, HKLM, HKCU, HKU and HKCC), and each of them contains a nested tree structure that serves a specific role in the system. But as one tries to dig deeper and understand how the registry really works internally, things may get confusing really fast. What are hives? How do they map or relate to the top-level keys? Why are some HKEY root keys pointing inside of other root keys (e.g. HKCU being located under HKU)? These are all valid questions, but they are difficult to answer without fully understanding the interactions between the user-mode Registry API and the kernel-mode registry interface, so let\'s start there.The high-level view

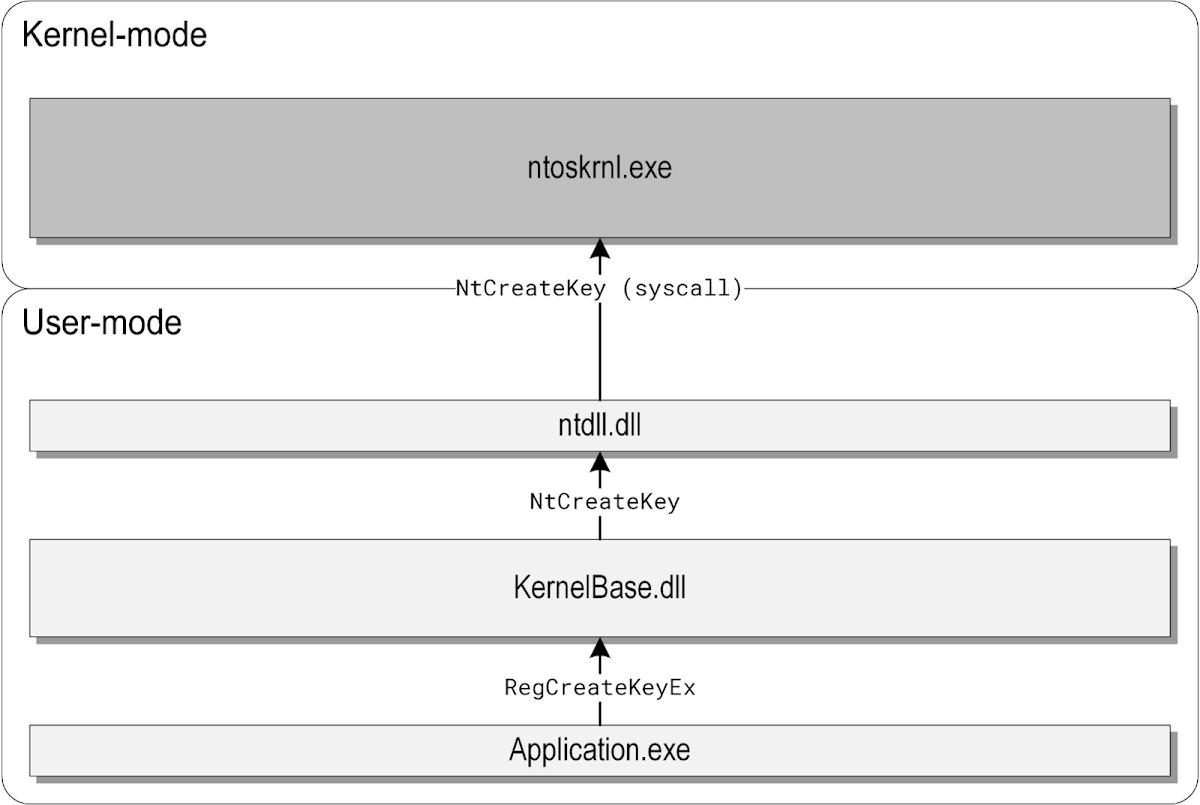

A simplified diagram of the execution flow taken when an application creates a registry key is shown below:

In this example, Application.exe is a desktop program calling the documented RegCreateKeyEx function, which is exported by KernelBase.dll. The KernelBase.dll library implements RegCreateKeyEx by translating the high-level API parameters passed by the caller (paths, flags, etc.) to internal ones understood by the kernel. It then invokes the NtCreateKey system call through a thin wrapper provided by ntdll.dll, and the execution finally reaches the Windows kernel, where all of the actual work on the internal registry representation is performed.

In this example, Application.exe is a desktop program calling the documented RegCreateKeyEx function, which is exported by KernelBase.dll. The KernelBase.dll library implements RegCreateKeyEx by translating the high-level API parameters passed by the caller (paths, flags, etc.) to internal ones understood by the kernel. It then invokes the NtCreateKey system call through a thin wrapper provided by ntdll.dll, and the execution finally reaches the Windows kernel, where all of the actual work on the internal registry representation is performed.

|

Tool Vulnerability Threat Legislation Technical | APT 17 | ★★★ | |

| 2023-01-23 20:14:17 | Blast from the Past: How Attackers Compromised Zimbra With a Patched Vulnerability (lien direct) | Last year, I worked on a vulnerability in Zimbra (CVE-2022-41352 - my AttackerKB analysis for Rapid7) that turned out to be a new(-ish) exploit path for a really old bug in cpio - CVE-2015-1194. But that was patched in 2019, so what happened? (I posted this as a tweet-thread awhile back, but I decided to flesh it out and make it into a full blog post!) cpio is an archive tool commonly used for system-level stuff (firmware images and such). It can also extract other format, like .tar, which we'll use since it's more familiar. cpio has a flag (--no-absolute-filenames), off by default, that purports to prevent writing files outside of the target directory. That's handy when, for example, extracting untrusted files with Amavis (like Zimbra does). The problem is, symbolic links can point to absolute paths, and therefore, even with --no-absolute-filenames, there was no safe way to extract an untrusted archive (outside of using a chroot environment or something similar, which they really ought to do). Much later, in 2019, the cpio team released cpio version 2.13, which includes a patch for CVE-2015-1194, with unit tests and everything. Some (not all) modern OSes include the patched version of cpio, which should be the end of the story, but it's not! I'm currently writing this on Fedora 35, so let's try exploiting it. We can confirm that the version of cpio installed with the OS is, indeed, the fixed version: ron@fedora ~ $ cpio --version cpio (GNU cpio) 2.13 Copyright (C) 2017 Free Software Foundation, Inc. License GPLv3+: GNU GPL version 3 or later . This is free software: you are free to change and redistribute it. There is NO WARRANTY, to the extent permitted by law. Written by Phil Nelson, David MacKenzie, John Oleynick, and Sergey Poznyakoff. That means that we shouldn't be able to use symlinks to write outside of the target directory, so let's create a .tar file that includes a symlink and a file written through that symlink (this is largely copied from this mailing list post: ron@fedora ~ $ mkdir cpiotest ron@fedora ~ $ cd cpiotest ron@fedora ~/cpiotest $ ln -s /tmp/ ./demo ron@fedora ~/cpiotest $ echo 'hello' > demo/imafile ron@fedora ~/cpiotest $ tar -cvf demo.tar demo demo/imafile demo demo/imafile ron@fedora ~/cpiotest $ | Tool Vulnerability | APT 17 | ★★★★ | |

| 2021-10-14 17:20:00 | Topic-specific policy 3/11: asset management (lien direct) |  This piece is different to the others in this blog series. I'm seizing the opportunity to explain the thinking behind, and the steps involved in researching and drafting, an information security policy through a worked example. This is about the policy development process, more than the asset management policy per se. One reason is that, despite having written numerous policies on other topics in the same general area, we hadn't appreciated the value of an asset management policy, as such, even allowing for the ambiguous title of the example given in the current draft of ISO/IEC 27002:2022. The standard formally but (in my opinion) misleadingly defines asset as 'anything that has value to the organization', with an unhelpful note distinguishing primary from supporting assets. By literal substitution, 'anything that has value to the organization management' is the third example information security policy topic in section 5.1 ... but what does that actually mean?Hmmmm. Isn't it tautologous? Does anything not of value even require management? Is the final word in 'anything that has value to the organization management' a noun or verb i.e. does the policy concern the management of organizational assets, or is it about securing organizational assets that are valuable to its managers; or both, or something else entirely? Well, OK then, perhaps the standard is suggesting a policy on the information security aspects involved in managing information assets, by which I mean both the intangible information content and (as applicable) the physical storage media and processing/communications systems such as hard drives and computer networks?Seeking inspiration, Googling 'information security asset management policy' found me a policy by Sefton Council along those lines: with about 4 full pages of content, it covers security aspects of both the information content and IT systems, more specifically information ownership, valuation and acceptable use:1.2. Policy Statement The purpose of this policy is to achieve and maintain appropriate protection of organisational assets. It does this by ensuring that every information asset has an owner and that the nature and value of each asset is fully understood. It also ensures that the boundaries of acceptable use are clearly defined for anyone that has access to This piece is different to the others in this blog series. I'm seizing the opportunity to explain the thinking behind, and the steps involved in researching and drafting, an information security policy through a worked example. This is about the policy development process, more than the asset management policy per se. One reason is that, despite having written numerous policies on other topics in the same general area, we hadn't appreciated the value of an asset management policy, as such, even allowing for the ambiguous title of the example given in the current draft of ISO/IEC 27002:2022. The standard formally but (in my opinion) misleadingly defines asset as 'anything that has value to the organization', with an unhelpful note distinguishing primary from supporting assets. By literal substitution, 'anything that has value to the organization management' is the third example information security policy topic in section 5.1 ... but what does that actually mean?Hmmmm. Isn't it tautologous? Does anything not of value even require management? Is the final word in 'anything that has value to the organization management' a noun or verb i.e. does the policy concern the management of organizational assets, or is it about securing organizational assets that are valuable to its managers; or both, or something else entirely? Well, OK then, perhaps the standard is suggesting a policy on the information security aspects involved in managing information assets, by which I mean both the intangible information content and (as applicable) the physical storage media and processing/communications systems such as hard drives and computer networks?Seeking inspiration, Googling 'information security asset management policy' found me a policy by Sefton Council along those lines: with about 4 full pages of content, it covers security aspects of both the information content and IT systems, more specifically information ownership, valuation and acceptable use:1.2. Policy Statement The purpose of this policy is to achieve and maintain appropriate protection of organisational assets. It does this by ensuring that every information asset has an owner and that the nature and value of each asset is fully understood. It also ensures that the boundaries of acceptable use are clearly defined for anyone that has access to |

Tool Guideline | APT 17 |

1

We have: 3 articles.

We have: 3 articles.

To see everything:

Our RSS (filtrered)